Complacency, Comfort and Conflict

Corrupt leadership, failing institutions, a depraved culture bereft of ethical and moral virtues – this is how last week's piece characterized modern America. The signs are undeniable and yet, it is not enough to say that power corrupts or that the natural aristocracy is no longer in control. When has power not corrupted, and when has rule by a few, ostensibly virtuous elites, made for a good and growing society? This cynical look at America, born of the nihilistic psychology of Freud, Nietzsche and Dostoyevskian characters takes us to the brink of the existential. That we lack the passion, creativity and motive force of previous eras is self-evident, but why is that the case, and can it explain economic stagnation?

There is a dualism to motivation that comes from Machiavelli's previously mentioned fear/love dichotomy. People tend to act out of fear or love, and fear is the more consistent but the lesser of the two motivators. Stagnation may be caused by complacency or paralysis, two equally fear based ideologies. The former disposition, produced by cosseted cocoons of comfort, rejects change and the latter, a pessimistic form of existentialism, doubts human progress. Whether the primary explanation is economic, natural or cultural, their roots all trace back to a lack of motivation. By examining the two variants of malaise, comfort and pessimism, I hope to illuminate major stumbling blocks on path of progress.

Prophecy of Hazards: The Failure of Imagination

Last week I began by asking readers to engage in some self-reflection about their status in society. Those who have thoughtfully read with Tyler Cowen's The Complacent Class, David Brooks' Bobos in Paradise or Ross Douthat's The Decadent Society have likely engaged in this sort of navel gazing before. Taking Cowen as our guide, we can explore the failure of imagination and complacency that he describes like this:

You can think of this [social stasis] as detailing the social roots for the resulting slow growth outcome and explaining why that economic and technological stagnation has lasted so long and why, for the most part, it has failed to reverse itself.

Sadly, the villain is us. Most Americans don’t like change very much, unless it is on terms that they manage and control, and they now have the resources and the technology to manage their lives on this basis more and more, to the country’s long-run collective detriment. America declines in the sense that it is losing the ability to regenerate itself in the ways it did previously...

Brooks and Douthat make compelling arguments too, with more spiritual conclusions, but let us stick with Cowen for explaining the complacency view of motivation before turning to any conclusions. Cowen provides two main reasons for a lack of motivation. The first is better matching throughout society.

Matching manifests itself in meritocracy, sorting and efficiency. We have discussed meritocracy at length already, but in this context it is important as a form of efficient sorting of human capital. Other forms of sorting – who we have families with, what media we consume, where we live and how we spend our time – have become hyper-optimized. Eking out marginal gains in efficiency leaves less slack in the system. Less room for creativity. Fewer chances to go off-trail. Greater risks for attaining some perceived future maximum of status.

The second reason Cowen gives is the pervasiveness of calm and safety. As with meritocracy, we have examined the theme of risk aversion in the prior section on culture, but just as meritocracy is to matching, so risk aversion is to calm and safety. The personal choices we make to cocoon ourselves and our loved ones not only has aggregate cultural effects, but also personal psychological and spiritual ones. The wellness-industrial complex thrives off our desire for calm. With no shortage of meditation apps, soothing scent diffusers, journaling regimens and sleep accessories, our obsession with therapeutic culture, as Lasch calls it, is the ideal vessel to pour our modern anxieties into. What are we so anxious about anyways? The counter-culture of the 1960s and 1970s has also mostly been accepted into the mainstream. Protest movements from women's rights to civil rights, to students rights and gay rights have turned the tide of popular opinion. Rock and rap, once seen as having deleterious effects on the youth are now accepted, celebrated and even seen as uncool parts of mainstream music. Drug use is tolerated and drug abuse is medicalized. Even tattoos, which used to signal being an outsider, a dissident, a risk taker, are now sported by more than half of women ages 18-49. As a much more tolerant society (a very good thing!), we are also much more conflict avoidant and neurotic personally.

What are the effects of these changes? Cowen claims society is more segregated in all sorts of ways. Obviously by race, but also by age and class. Companies are also pulling away from one another with the rise of what Cowen calls "superstar firms." He worries about how few Americans are directly involved in innovation today and how a lack of job mobility preventing the diffusion of productivity across firms. As we get better at tracking and directing every aspect of our (and our children's) lives we give up some dynamism and serendipity. The consequences of this are slow growth, which he predicted in 2017 would lead to the burgeoning of crime, new campus protests and government instability.

His track record for prediction is, unfortunately, is looking pretty good. Cowen ends his book with a section on global instability, saying in particularly prescient prose, "[W]e are going to find out far more about how the world really works than we ever wanted to know." By acknowledging the pessimistic existential explanation only at the very end of his book, Cowen is indicating that although he knows about this risk, it is more productive to focus on getting out of our own comfort zones than worrying about these tail risks.

Although Brooks and Douthat trace a similar argument, unlike Cowen, they come to an explicitly spiritual conclusion. Their hope is that religious revival and personal spiritual growth will break the bubbles we've self-sorted into and lead to a more thoughtful, communal and virtuous society. Nearly two and a half decades before Brooks and Douthat, Lasch had this to say, "In the commentary on the modern spiritual predicament, religion is consistently treated as a source of intellectual and emotional security, not as a challenge to complacency and pride. Its ethical teachings are misconstrued as a body of simple commandments leaving no room for ambiguity or doubt.” In Lasch's telling, Christianity is subversive, and it is culture – first as directed by The Church, and now by scientific rationalism –that is stifling. Therapeutic culture specifically calms our existential anxieties. Brooks and Douthat's spiritual solution also indirectly point towards apocalypse, because Christianity, we often forget, is an apocalyptic religion. While Cowen directs us to look away from apocalypse, and Brooks and Douthat direct us to look to God, Lasch directs our attention towards apocalypse.

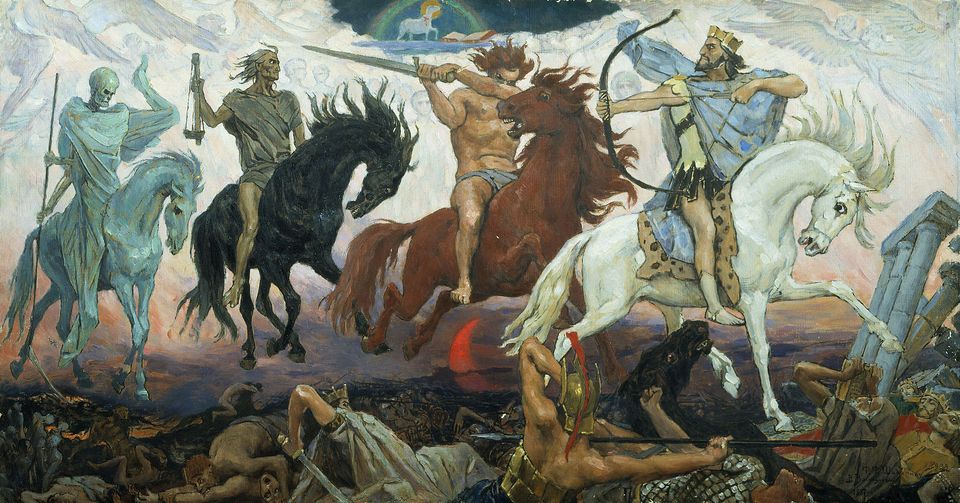

Take Peace From The Earth

For nearly all of human history, apocalypse has been both imminent and unimaginable. Imminent because we lacked mastery. Catastrophe could befall us at any time, whether it be flood, invasion, disease or famine. Unimaginable because no society that was wiped out lived to tell about how it happened. With the help of the state, the Enlightenment, and scientific rationalism, we began to master the environment, war, medicine and agriculture. Then, for a brief period, apocalypse seemed preventable. People were motivated and optimistic. Progress barreled into the 20th century. By the 1960s and 70s, apocalypse was not only imaginable but palpable. How this happened, whether war is the father of innovation and if we can grow faster without disturbing our uneasy peace are the three most important questions of our time.

In James C. Scott's Seeing Like A State, he identifies four elements of failed utopian schemes. The first he calls "the administrative ordering of nature and society." If this sounds an awful lot like matching, meritocracy and sorting, that's because it is, but on a state level. The second element is "high modernism" a term he defines as "strong, one might even say muscle-bound, version of the self-confidence about scientific and technical progress." The third element is authoritarianism in service of high modernism, and the fourth is a weak civil society incapable of resistance. It is elements three and four that he mainly blames for failure, although one and two are necessary preconditions. Scott emphasizes the importance of diversity, local knowledge, incrementalism, revocability and serendipity, but he has little to say about civil society. Still, his instructions on authoritarianism in the service of high modernism are useful.

If one were required to pinpoint the "birth” of twentieth-century high modernism, specifying a particular time, place, and individual—in what is admittedly a rather arbitrary exercise, given high modernism’s many intellectual wellsprings—a strong case can be made for German mobilization during World War I and the figure most closely associated with it, Walther Rathenau. German economic mobilization was the technocratic wonder of the war.

War, revolution and economic collapse, he says, sharply increase the appeal of authoritarianism and weaken civil society. War, particularly since the invention of nuclear weapons, is the most obvious potential apocalypse, but due to the defensive mechanisms of calm and safety, it has become taboo to speak of such things.

A couple of ways in which we can speak about war is in the context of liberty and innovation. Today we speak about self-determination and the struggle for independence. The founding fathers of America, despite fighting for their own freedom from colonial rule, did not speak of war in such terms:

Of all the enemies to public liberty war is, perhaps, the most to be dreaded, because it comprises and develops the germ of every other. War is the parent of armies; from these proceed debts and taxes; and armies, and debts, and taxes are the known instruments for bringing the many under the domination of the few.

James Madison, above, echoes Scott, who noted that two types of war in particular, revolution and colonialism, could sew the seeds of authoritarianism, because in both, civil society is weak and the technocratic promise of high modernism is ripe for social engineering experiments to remake society either in opposition to the ancien régime or as a project in welfare colonialism. Scott's view of war is in line with the Leninist perspective of war as a class struggle. Marx, who lived before the Weimar Republic and Rathenau's war industrialism, showed wavering support for national defense, sometimes supporting it and sometimes criticizing it on the basis of class. Lenin, however, made it clear that there are just two wars in his view, revolutionary and imperial. "Defensive" or "offensive" descriptions do not apply, in his view, since all conflict is class conflict.

With this in mind, we may examine whether the claim that war contributes to economic growth and, more provocatively, whether it is necessary for growth. To be clear, the modern economic and international relations theory consensus denies both of these points. Chris Blattman, author of Why We Fight, cites "A large literature [that] has shown how wars collapse economies." For an overview of Blattman's five theories of why we fight see part I and part II of his lecture on conflict from his class on political development. Most modern international relations theorists chalk wars up to a miscalculation. Returning to the revolutionary versus imperial framing of war, we can find a more rigorous and perhaps less biased view than Lenin from two economists who wrote about Scott's birth of high modernism and WWI mobilization, Joseph Schumpeter and Thorstein Veblen.

Veblen and Schumpeter, both critics of capitalism and authors of Imperial Germany and the Industrial Revolution and Imperialism and Social Class, respectively, have much to say about high modernism. Veblen in particular proposed a utopian technocracy in which engineers, not businessmen, would control companies. On the profitability of war Veblen has this to say:

The resulting state of the case at the close of the war period, therefore, so far as bears on the point immediately in question, may be summarized. Business men engaged with industries subject to the war demand will have gained, while industry in other lines will have lost, though proportionately less; industrial property (plant and securities) will have been recapitalized, on a thinner equity and an enhanced rate of dividends, at an aggregate valuation probably exceeding that of an equivalent equipment before the war; the effectual outstanding capitalisation (largely funded and therefore irrevocable) of the industrial community will presumably be no smaller than it was before the war loans were floated.... such a season of war prosperity should be followed by a liquidation, to bring the aggregate capitalisation into passable correlation with earning capacity, and to determine the resultant ownership of the net earnings.

Schumpeter, on the other hand, did not wish for the demise of capitalism, but simply argued that its success would inevitably lead to corporatism and the death of entrepreneurship, paving the way for socialism.

It is in the nature of a capitalist economy—and of an exchange economy generally—that many people stand to gain economically in any war. Here the situation is fundamentally much as it is with the familiar subject of luxury. War means increased demand at panic prices, hence high profits and also high wages in many parts of the national economy. This is primarily a matter of money incomes, but as a rule (though to a lesser extent) real incomes are also affected. There are, for example, the special war interests, such as the arms industry. If the war lasts long enough, the circle of money profiteers naturally expands more and more—quite apart from a possible paper-money economy. It may extend to every economic field, but just as naturally the commodity content of money profits drops more and more, indeed, quite rapidly, to the point where actual losses are incurred. The national economy as a whole, of course, is impoverished by the tremendous excess in consumption brought on by war. It is, to be sure, conceivable that either the capitalists or the workers might make certain gains as a class, namely, if the volume either of capital or of labor should decline in such a way that the remainder receives a greater share in the social product and that, even from the absolute view-point, the total sum of interest or wages becomes greater than it was before. But these advantages cannot be considerable. They are probably, for the most part, more than outweighed by the burdens imposed by war and by losses sustained abroad. Thus the gain of the capitalists as a class cannot be a motive for war—and it is this gain that counts, for any advantage to the working class would be contingent on a large number of workers falling in action or otherwise perishing. There remain the entrepreneurs in the war industries, in the broader sense, possibly also the large land-owner—a small but powerful minority. Their war profits are always sure to be an important supporting element. But few will go so far as to assert that this element alone is sufficient to orient the people of the capitalist world along imperialist lines. At most, an interest in expansion may make the capitalists allies of those who stand for imperialist trends.

Schumpeter's analysis is in line with the popular ideology of his time, made manifest in The Great Illusion by Norman Angell. This view held that free trade and a web of alliances would prevent world war, and the cost of war would be so high that no nation would dare risk an attack. The illusion in the title is the "optical illusion of conquest," by which Angell meant "national safety can be secured by means other than military force."

The book's timing was unfortunate not only for being disastrously incorrect on the eve of The Great War, but also for what it got right that was promptly forgotten when war began. Following Angell's dubious argument that if small but wealthy states can find diplomatic and economic means of security, so can large ones, he makes an excellent analysis of "the impossibility of confiscation." Arguing from the perspective of an industrialized free-trade country, half a century since the end of English mercantilism and 100 years after Adam Smith and David Ricardo, Angell lays out six points demonstrating how the supposed benefits of a German war against Great Britain were illusory:

- Complete destruction of the British population is also destruction of its labor force and market.

- Confiscation of British capital stock would lower the value of German credit and equities because the economies are so intertwined.

- Extracting tribute (reparations) from Britain would disrupt financial flows and trade.

- German merchants would not face any less competition from British merchants if Germany conquered Great Britain.

- Conquering Great Britain may add revenue and population to Germany, but it wealth per capita is what matters.

- The British Empire is not one of military occupation, but of custom, trade and alliance, none of which would change in defeat.

While we must reserve some skepticism, particularly of the freedom for colonies to act freely, Angell's general premise about the lack of benefits from war are correct. Ultimately Germany and Great Britain did go to war, but not because it benefited Germany economically, and in the aftermath of the Allied victory, Great Britain entered a period of economic stagnation followed by the Great Depression.

If the First World War debunked the war as profiting imperialism and confirmed the Veblen-Schumpeterian view that war is a net negative with some special interests benefiting, what did we learn from World War II? Before and after the war, John Maynard Keynes popularized the view that war spending, like all fiscal stimulus, can grow the economy. Keynes' more subtle point about spending – that stimulus works best to "prime the pump" and it might be better spent on infrastructure projects with a high multiplier – are sometimes lost in the war-spending debate.

Finally, there are the libertarian, skeptical and cynical views of the political economy of war. Ludwig von Mises, President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Major General Smedley Butler echo Scott's warning about the coercive power of the state when used in conjunction with high modernism. Mises is quick to point out that war is disadvantageous for the world economy, but certain states or sectors may profit from war. Eisenhower's famous last speech in which he coined the phrase "military-industrial-complex," is also such a warning. Following WWI Butler published a shocking account of war profiteering called War Is A Racket.

The primary question for us, however, is war's relationship to motivation and productivity growth. As it regards innovation and invention, war is often touted as a great motivator and, in Scott's words, a "force majeure." Steve Blank's Secret History of Silicon Valley is just such an argument that war can be a catalyst for innovation. Anecdotally, we can observe new technologies and the wars that spurred them, such as railroads and telegram for the Civil War, airplanes and electricity for WWI, nuclear energy and radar for WWII and computers and satellites for the Cold War. A number of academic papers also support the hypothesis that war may be additive or even necessary for economic growth. If this is the case, then perhaps the slow growth of the last 50 years is a consequence of Pax Americana.

Apocalypse How?

Proving motive is always challenging and between the two hypotheses of complacency or existential dread, I'm not sure which is less appealing. We live in the era of the imaginable and inevitable apocalypse. As bad as it feels, it seems important to acknowledge that truth rather than turn away from the discomfort. Still, acknowledgment is only the first, but an important step, towards a solution. We must also find ways for imagination to triumph, without an escalation of violence.

Apocalypse in Ancient Greek means to reveal. That is where the biblical Book of Revelation gets its name. The risk of revealing disturbing truths about the relationship between our need for an enemy and our capacity for innovation may be our undoing. Scott's "coercive power of the state" in service of "administrative ordering" has consequences not just for better matching and existential risk, but also the homogenization of society and the media culture of high modernism. Next week's installment deals with this most enigmatic challenge.